I'm prepare move to new home

A simple life, far removed from the dense crowds and vast machinery of society—a secluded place where peace and freedom prevail precisely because of its remoteness.

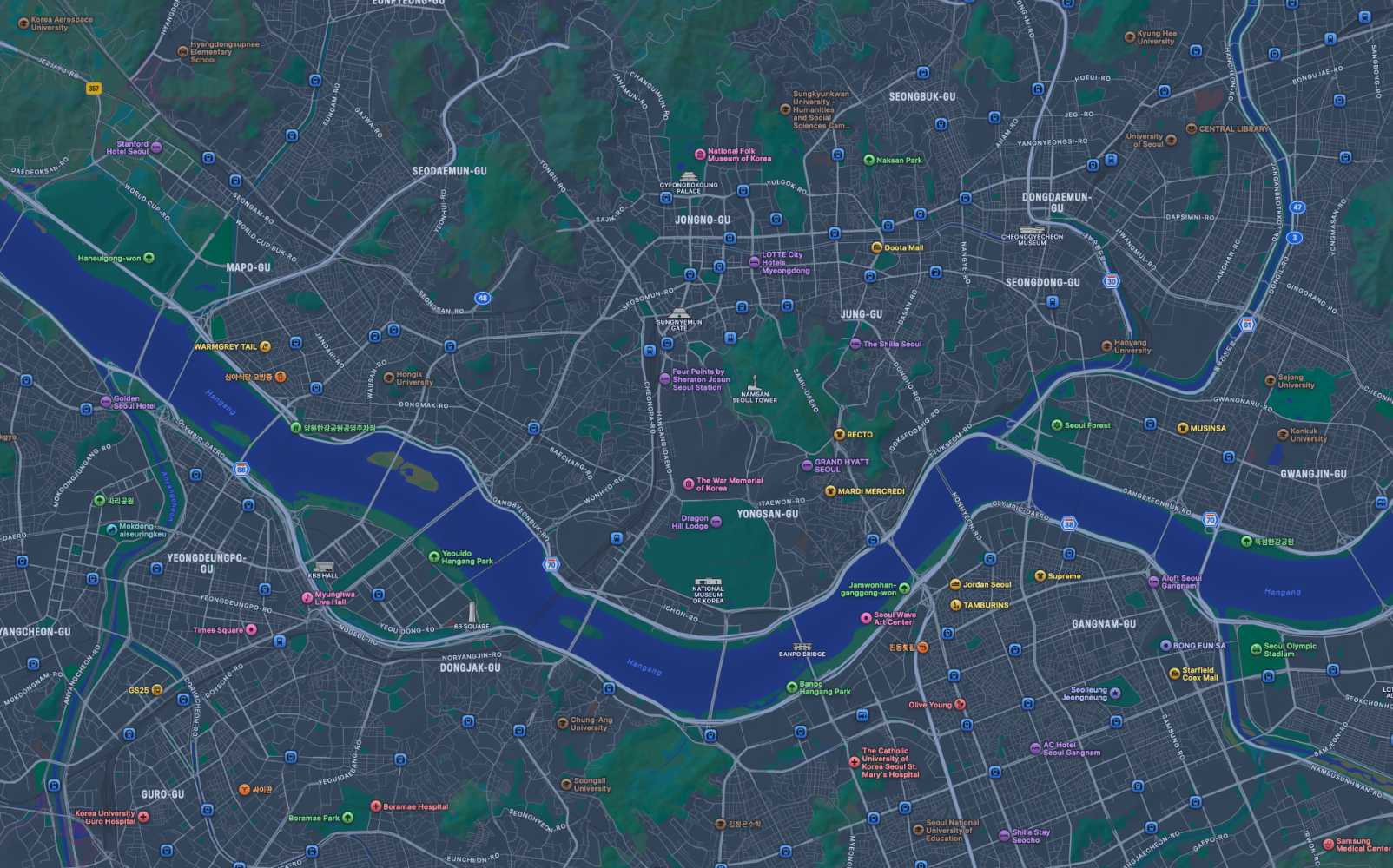

Lately, when I visit Seoul, a few thoughts come to mind. When I see the square-shaped buildings with uniformly sized windows, they remind me of poultry cages—facilities designed solely for feeding and egg production. Everywhere is crowded with people, and it feels as though the same rules and standards applied to objects are also imposed on human beings, making the place feel constrained and unfree.

One chooses to leave behind the vast machinery of mass society and moves toward a place of low population density. In doing so, one gradually distances oneself from overcrowded spaces and begins to encounter small, localized communities composed of neighbors, friends, and cherished individuals. Throughout human history, the most fundamental form of interpersonal relationship has been the small community—one not mediated by any religion in the broad sense, such as systems of contracts or codified laws. In order to avoid excessive friction with strangers, humans began to build large-scale societies under shared belief systems—capitalism, democracy, socialism, or theistic religions—each functioning as a kind of faith.

But civilization itself is a relatively recent phenomenon, emerging only around 10,000 years ago. Unfortunately, over the course of an evolutionary history incomparably longer than that, humans did not evolve to prefer invisible or indefinite relationships with countless strangers. Our core relational instincts begin with those dearest to us—those immediately around us.

In seeking to fulfill the demands of industrial society, people lose their personality and humanity. They prioritize the workplace over family, sacrificing the warmth of loved ones to earn money—mere paper symbols of value. The very people who should be the source of life’s meaning, our beloved families, become obstacles in the path toward participating in the industrial order. In the modern system, all must become laborers—regardless of age or gender—in service of the social machine. Those who refuse this and choose family instead are labeled as failures, as dropouts unfit for societal success. From a young age, we are taught that we must never become such people.

My aspiration is to escape from this religion called industrial society and to live a life that gratefully cherishes the tangible things close to me. In order to reclaim my lost personhood, to decide for myself what matters in life, and to pursue a path of autonomy where I alone choose the direction of my existence, I choose to leave—even if that means heading to a place regarded as remote or underdeveloped.